The EA psyche

Radical empathy and taking ideas seriously

My first post got a frankly bewildering number of likes and shares — thank you and welcome to all my new subscribers! Since many of you don’t know me at all, let me take a second to introduce myself. In my day job I work on trying to understand and track extreme risks from AI agents at METR. Before that, I spent almost a decade at Coefficient Giving. I write about AI futurism over at Planned Obsolescence, and this is my personal blog.

A lot of this blog will be, directly or indirectly, about effective altruism (EA). I’ve been deeply involved in EA for 15 years, since I was a high school freshman.1 In college I co-founded the EA Berkeley student club and co-taught a class about EA. In 2016, our club put on the first EAGxBerkeley, where I gave an intro to EA talk that’s still on the EA resources page and is sometimes featured in intro to EA courses and seminars ten years later.

A lot of EAs are the type who don’t like labels, who like to “keep their identity small,” who are always “adjacent” to something.2 I think this has its virtues, but is often a bit too precious. I like labels. I like how I can say “I’m an EA, a rationalist, and a woman” and this short sentence compresses me so efficiently. And I like wearing the label and giving talks at EA Globals because I think EA is really great and way more people should get into it.

I also like that when you have a label for what you are, you can more easily look in on the thing-you-are from the outside. I recommend Ozy’s excellent post series for an anthropological guide to what EAs actually believe. I think most of the more specific beliefs he talks about are downstream of two core EA psychological traits:

Taking ideas seriously. Most people don’t change anything significant about how they act after perceiving a pattern of squiggles on a screen. If they encounter arguments like the drowning child thought experiment or the Simulation hypothesis (which they probably won’t), they go “huh” and move on with their day. EAs are very unusually willing to change our lives around based on explicit logical arguments. We are very unusually unattached to the intuitions we’ve picked up about what’s “normal” and the “done thing,” and unusually likely to bet that first-principles reasoning can beat “expert consensus.”3 We’re more likely to do Lifecycle Investing or buy AI stocks on the basis of arguments about the technologies, we were more likely to stock up on PPE (and short global markets) in January and February 2020, we’re more likely to be intensively analytical about our personal lives (see dating docs), we’re more likely to be early adopters of novel medical interventions like GLP-1s or a genetically engineered bacterium that prevents cavities.

Radical empathy. EAs strive not to care about some beings more than others just because they are closer to us in space or time, just because we share a country or race or species or other group membership with them,4 or for any purely “aesthetic” reason (even as we debate what counts as “aesthetic” vs “substantive”). We strive not to care more about Americans than about Ugandans or Iranians or Chinese. We strive not to care more about pandas than pigs. We strive not to care more about humans than non-human animals except insofar as we have arguments that humans have a greater capacity for well-being or suffering (however we define that). We strive not to care more about sentient life in this universe than life in other universes. We strive not to care more about biological creatures than we do about digital minds, including the AIs we’re building now. This is not natural, it takes continuous effort to exercise the kind of discipline and imagination needed to act in accordance with radical empathy.

Radical empathy doesn’t necessarily follow from taking ideas seriously or vice versa, but in actual humans, they are very correlated traits. They also structurally amplify one another. No one is born caring about the Tegmark IV multiverse, so you have to argue yourself into it (i.e., taking ideas seriously generates radical empathy). And if you do decide you care about Tegmark IV then the only path to try to directly impact the thing you care about goes through abstract analysis, you can’t imitate what worked well for others or learn by trial and error (i.e., radical empathy forces taking ideas seriously).

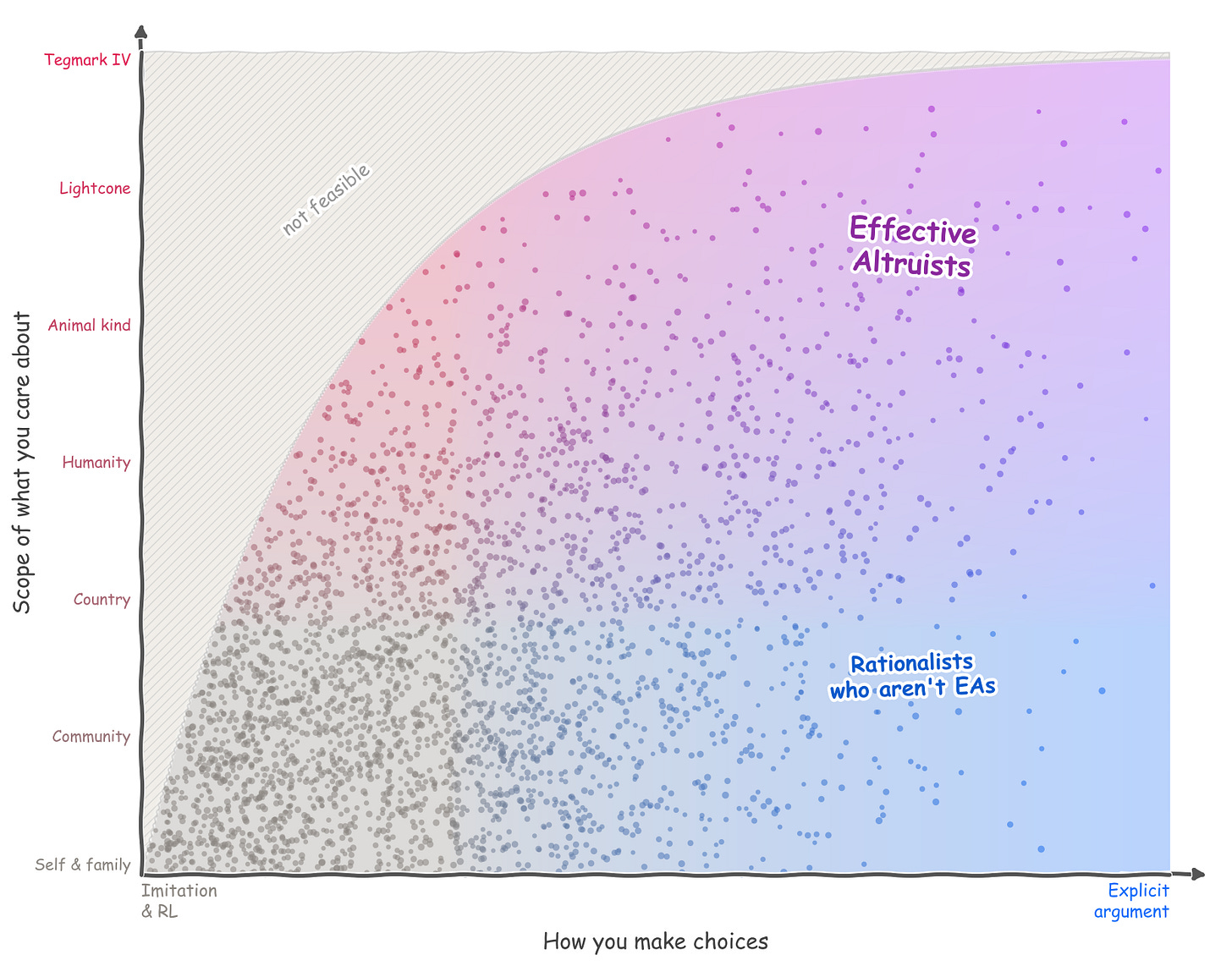

If you plot the two traits against one another, there’s a region of the graph — “aiming to directly benefit exotic distant beings while making decisions using intuitive learned heuristics” — that’s impossible to reach.

The further you go to the top right of this graph, the more you’ll code as “EA” to fans and haters alike. I was born very EA, and spending over a decade in the heart of the community has made me even more EA.

But I’m definitely not maximally EA (I mean obviously no one is, but I regularly talk to people distinctly more EA than me on these axes). I’ve always been more intuitively uncomfortable with purely philosophical thinking leading to crazytown conclusions than many of the people I hang out with every day. And the deeper I go in my career, the more salient it becomes to me that in the domains they can access, imitation learning and RL perform so much better than abstract argument.

Even in a whole career dedicated to trying to fill the lightcone with goodness, most of your learning and growing has to come from imitation and RL.5 That’s just how it works to build skills. This sucks for you if your goal is to positively shape the fate of the Tegmark IV multiverse, because you’ll always have vast uncertainty about whether the feedback signals you have available to train on (people reading your posts or passing your policies) are all that correlated with the ultimate unobservable goal. Someone whose goal in life is to make as much money as possible gets the luxury of learning how to do their thing much more efficiently than you can learn how to do your thing.

In fact, I’m selecting my goals to be ones that have better feedback loops. My reluctance to rely more heavily on abstract argument is constraining my ability to practically go further on radical empathy. When you’re mostly uninvested in trying to directly influence X, it becomes a more academic question how much you care about X. In some sense I care a lot about helping beings outside the simulation we might be in (probably are in?) right now, or about making acausal trade with distant parts of the multiverse go well, but these considerations don’t really enter into my decisions on a practical level. Instead, I gravitate to stuff like trying to help people understand where AI might be in six months.6

And even though I think EA is really great, it’s a high-variance way of being. When someone decides to take ideas seriously and ambitiously shape the world according to them, the rest of us suddenly become intensely invested in the exact particulars of those ideas. Many hardcore EAs found their way to EA after first having been hardcore about Christianity. And though some of my friends might protest, I’d bet today’s hardcore EAs would have been disproportionately likely to be hardcore Marxists during the Great Depression.

When you get to the heady zone in the top right of the graph, I’m feeling pretty nervous unless you’ve cultivated a thousand more delicate qualities — carefulness, humility, curiosity, self-awareness, humor, judgment, patience, taste — alongside the core traits that define EAness.

In fact, I think most hardcore EAs do have these other little virtues. My friends and mentors are deeply good people, in a rich and full sense, and that’s what makes it work for them to be crazy EAs. In my view, the EA subculture we’re embedded in encodes some genuine wisdom about what it takes to be super hardcore — to actually work on space governance or acausal trade — with grace and, well, effectiveness.

In my standard elevator pitch I tend to tell people it started with reading The Life You Can Save when it came out in 2009, which would be the summer after eighth grade. But in reality I was already a New Atheist reading blogs like Julia Galef’s in middle school, and had multiple independent links to LessWrong from there. I was also already very concerned about global poverty (e.g. in elementary school I had a period where I religiously played the World Food Programme’s trivia game where they supposedly give farmers a bag of rice if you answer quiz problems correctly), which probably had something to do with finding and reading TLYCS in the first place. Basically as soon as I heard the concept, I knew this was what I was.

A few years ago I was at a conference called the “EA Leaders’ Forum” (they changed the name later), in which roughly ⅓ of attendees raised their hand in response to the question “Do you consider yourself to be an EA?”

To be clear, this is in fact a trait we have in common with flat Earthers and UFOlogists. For most people most of the time, “thinking for yourself” and “following the logic” is not the most efficient way to get good outcomes in real life, a fact that rationalists and EAs (okay, fine, Scott Alexander) have spilled a lot of ink grappling with. As Ozy says, “We respond to concerns about taking ideas seriously in part by coming up with a whole new set of ideas to take seriously! Reorienting your entire life because you read an essay is very effective altruist, even if you’re reorienting it towards being less affected by essays.”

Of course, EAs, like all human beings, certainly act as if they care more about themselves and their loved ones than about strangers. Most of us take plenty of time off work. Even those who, unlike me, consistently work 7 long days a week would skip work to visit their parents if they were dying. If they were in a burning building, they would instinctively try to save their significant other over an acquaintance with a higher-impact career.

Many EAs prefer to identify this with their genuine underlying values; i.e., they would say, “Yes, I care more about myself and my friends and family compared to strangers.” I lean in this direction. Other EAs take a more hostile attitude and think of it as weakness of will, or say that any apparent partiality toward themselves and their loved ones is merely instrumental (you need to take breaks to be more productive in the long run, you need a romantic partner to maintain motivation, you need to be nice to people around you to have a good reputation, etc).

Earlier on in your career, big picture abstract arguments can have a huge impact (”you should work on AI risk instead of climate change,” or “natural pandemics are much less risky than engineered pandemics”). But as you go deeper into something particular, it’s harder and harder for abstract arguments to radically change your course of action.

I think this is in part a skill / specialization thing — if I were (even) better at the kind of abstract argument relevant to long-termist cause prioritization, I would be (even) more of an EA in practice.

This is interesting - "And I like wearing the label and giving talks at EA Globals because I think EA is really great and way more people should get into it."

I also think EA is good and more people should get into it, but have found personally that not calling myself EA (for "small identity" reasons) has been better for helping other people get involved themselves.

They are either more sceptical people who seem to be put off by 'EAs', or they see EA as an all encompassing identity which meant if they cant give 10%+, go vegan, pivot their career and call themselves EA, that they should not get more into it.

That was an interesting post! I always enjoy reading quasi-anthropological reflections on EAs and Rats.

Myself, while I enjoy exploring ideas seriously (and have them influence my life) and have a great sympathy for a lot of EA's principles and goals, and even more so for specific people in the movement I interact with, I could likely never go beyond a very tepid adjacency. Radical empathy is something that completely fails to resonate with me at all, and when some thinking thread leads to what I feel are excessively absurd or demanding positions (like Pascalian Muggings) I find it very easy to apply some sort of boundedness and just chop away. But even if the EA path is not for me, I do feel it's likely net-positive for the world, and its externalities mostly just fall upon its practitioners.